This program is available in-person or virtually for a fee. Inquire with David. davidethanalexander@gmail.com or Instagram @natureintoaction

While the majority of foraging is done spring, summer and fall there are still many items of interest in supply on the winter landscape. The following are the primary bioregional forage that I’ve made use of in the winter months.

Like gardening at home, foraging helps increase my self reliance, helps me deepen my connection to nature and provides exciting ingredients in every meal.

There are many critical considerations before eating wild plants. I like to use Green Dean’s acronym I.T.E.M.

- Identification: You must make your own positive identification and confirm that it is not a poisonous lookalike.

- Time of Year: Some plants are best picked in a specific season.

- Environment: Only eat plants in clean growing environments (no pesticides, busy roadsides or dog park)

- Method of Preparation: Some plants require proper cooking to be safe to eat and also should be enjoyed in moderation.

WINTER MUSHROOMS

Winter Oyster Mushrooms (Pleurotus ostratus) are a mild tasting fungus found growing on dead wood in shelf like clusters with tight whitish gills running right into the short stem. The winter variety has a darker colored cap and is good table fare when properly cooked. Although some people get indigestion, so eat sparingly to start.

Wood Ear Mushrooms (Auricularia auricula-judae) have a delicate earthy flavor and can have a crunchy jelly texture and are popular in Chinese cuisine. Like tofu they pick up flavor in the cooking process. You can put them in your stir-fry last so they cook but do not become mushy. They can be dehydrated and rehydrated easily as well. In fact sometimes you find them dried in the forest if there hasn’t been any recent rains but then they swell up after a storm. They are high in iron like liver!

WINTER TEAS

Chaga Mushroom (Inonotus obliquus) is found on birch trees in the northeast and other northern latitudes. It is called kreftkjuke in Norway, which literally translates to “cancer fungus” due to its purported health properties. Studies have shown chaga to offer health benefits. The mushroom is dried, powdered, and used to make Chaga tea, extracts, or tinctures. When I camp, I’ll cut through it with a sawblade and make a tea out of the chaga sawdust or simmer small pieces until I get the color and strength I’m after. It has a nutty earthy flavor like some kinda fancy specialty coffee. It’s more common in the northeast but can still be found in smaller quantities in New Jersey.

Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) is a deciduous shrub found abundantly in our wooded wetland forests and often around woodland waterways. Tea is made out of the aromatic twigs and the glossy red fruit is used as an allspice. The birds usually pick the fruit in autumn to help fuel and fatten themselves up for migration and/or winter survival. The shrub grows 6-12 feet tall . If you ever looked for a native alternative to forsythia you may have seen this as a better choice option. It’s best to recognize the general shape of the shrub in winter and then scratch and sniff a twig tip to confirm identification with your sense of smell.

American Wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens) is a calcifuge, favoring acidic soil, in pine and hardwood forests. The berries I refer to as nature’s tic-tac’s and the green leaves I’ll collect sparingly so long as the population is abundant and use them to make a minty tasting tea. The active ingredient in the wintergreen leaves is methyl salicylate and historically has been extracted and used to flavor candy, medicine and chewing gum but it’s now chemically synthesized.

Sweet Black Birch (Betula lenta) and Golden (yellow) Birch (Betula alleghaniensis) is another favorite winter forage for use as a tea. The black birch has stronger flavor but the golden birch still has a strong scent of methyl salicylic acid similar to wintergreen. No other birches have the characteristic. They can be identified with their serrated oval shape leaves and pointed tip leaves that are alternatively growing on the stem. The black birch has platy firm bark with horizontal lenticels and the yellow has horizontal curly yellowish pieces more easy collected for fire starting.

Eastern White Pine (Pinus strobus) Needle Tea is another popular winter wild edible treat. The tree is easily identified with its cluster of five needles per fascicle. I spell out w h i t e as a trick to remember it. However, all pines are edible.. just avoid look alike plants like the yew! The hemlock tree makes a tasty tea and is not to be confused with the poison-hemlock herbaceous flowering plant. To make the pine needle tea, I like to take the freshest pine needle tips and bring a big handful of them to a boil and than immediately simmer with the lid on to trap those essential oils. You can add more to taste or let it simmer longer to find what you like. You could also drop in a pine needle branch like a tea bag and get some flavor but it won’t be as consistent of a recipe.

Staghorn Sumac (Rhus typhinatea) makes a wonderful drink and spice. You can buy a spice mix from the Foraged Feast at Northern New Jersey farmers markets or collect your own and dry it yourself. It’s best harvested before a rainstorm so the rain doesn’t wash the tangy malic acid away. You should also examine the sumac heads for bug damage and then taste test them to find the very best flavor. It’s possible to still find some clean enough to make a drink in early winter. Here is a recipe to make Sumac-Aide Tea!

Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora) is most prolific in North America as an invasive that can fruit large amounts of edible berries known as rosehips. They can be used to make a tea, to do so, mash the rose hips and steep them in hot water. They are best harvested after the first frost because they become soft and sweeter. Rose leaves as long as they are tender and thorny and flower petals are also edible. Rose hips are rich in vitamin C, carotene and a source of essential fatty acids.

Another prominent red berry on the landscape is from the invasive Japanese Barberry (Berberis thunbergii). The fruit holds on right through the winter months and is clearly visible within the small thorny twigs. The berries have a hint of sweet and a bit of tart but get sweeter with age and are used as a trail nibble, used in cookies, pies, jellies and drink mixes for the vitamin C.

WINTER GREENS

There are also greens available on the winter landscape as long as they are not snow covered and roots for harvest so long as ground allows entry. Sometimes moving some of the leaves on the forest floor reveals a salad underfoot. Traditionally, you may find recipes that call for horta or potherb which is referencing mixed wild or garden greens.

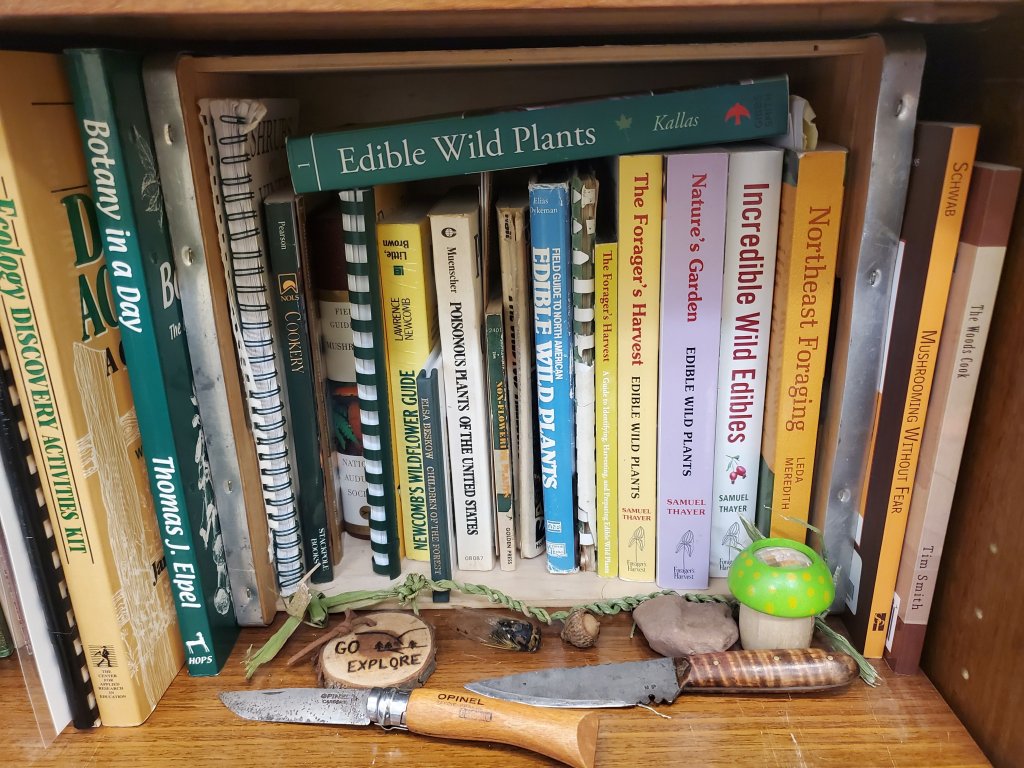

There are three kind of Cress that I find commonly. Watercress, Hairy Bittercress and Wintercress (yellow rocket). They are all mustard greens, somewhat bitter and stimulating to digestion, in the Brassicaceae family. The hallmark of Brassicaceae is the four petals of the flower but you won’t see that until April and into June. The family was formally called Cruciferae, a reference to the crucific pattern of the petals but botanists have made some rearrangements. All species of the mustard family are edible so recognizing the plant family can help determine edibility of many species. Thomas J. Elpel’s Botany in a Day book is the best resource that I’ve found for learning these techniques.

Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) I find often in small streams and seeps especially that form as a result of natural springs. The roots are white and stringy and attach loosely to the wet gravel. The conscientious forager should just snip the tops and allow the plant to continue to grow for future harvest although it’s not a native to North America. The plant is supposed to have more iron than spinach, more calcium than milk, more vitamin C than oranges, more folate than bananas and the same protein per calorie as chicken!

Hairy Bittercress (Cardamine hirsuta) is a favorite of foragers in wintertime when it appears as a basal rosette often in disturbed soils or around greenhouses and planting pots. It’s another member of the Brassicaceae mustard family and has tender edible greens and a root hot like horseradish. The leaf flavor is more mild than bitter and goes well in a salad or as a garnish to shine up a steak if you’re more carnivore than herbivore. The plant is full of vitamin C, calcium, magnesium, beta-carotene, and antioxidants. As the weather warms and the plant puts out seeds in pods called siliques

Wintercress (Barbarea vulgaris) also known as yellow rocket is a biennial that forms a rosette of leaves the first year and then bolts up with a stalk as long as 2 feet the second year. It is considered a noxious weed so go ahead and eat it to beat it. I find it on roadsides in soft sandy soil. It has vitamin A and C and is also known as scurvy grass or cress. The young leaves of the basal rosette are best harvested after the first frost as salad greens, The second year leaves are also tasty before the plant goes to flower as they become bitter afterwards. This bitter taste is common among plants when blossoming as an evolutionary trait that gives themselves better resistance to pests.

//Wintercress Photo on the way//

Chickweed (Stellaria media) is edible, nutritive and delicious! It’s a cool weather plant seen mostly in spring and fall but it can appear in winter as well if temperatures remain warm. The quarter inch oval shaped leaves grow opposite from each other on a stem that can be around a foot long with a line of “hair”. The inner stem is elastic, so if you pull it apart the outer part will separate.

Chickweed is also found adjacent to thermal refuges like in a city or suburb near a building that may absorb, reflect and/or radiate the sun’s warmth all day. The grayish painted concrete on the green house at my worksite reflects heat that allows chickweed to grow year round. According to Northern Architecture, the color of a building’s surroundings and surfaces influences how much radiation is reflected, and how much is absorbed. A building painted white reflects about three-quarters of the sun’s direct thermal radiation. Foragers may find a windfall as a result.

Field Garlic (Allium vineale) aka onion grass aka chives if you go to a fancy restaurant are available for harvest year round. It has long narrow hollow leaves with bulbs at the bottom. The whole plant smells of onions. You may have cut the grass before and gotten a full dose of the strong odor.

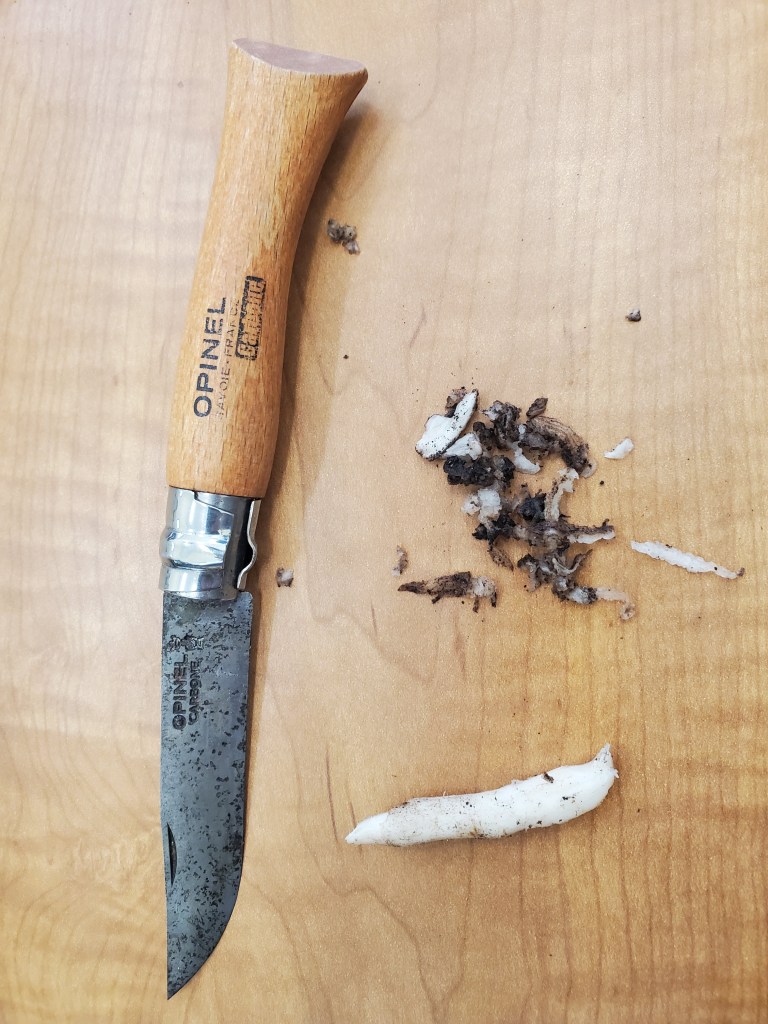

Thistle has edible parts available through the seasons. In winter the root can be dug up and eaten raw or cooked. The pictured plant is the first year root and rosette. There isn’t much of a root yet but it’s still a tasty treat and I’m happy to weed this individual spiny plant from this spot.

Cattail (Typha) rhizomes can be dug up in the winter months. The starchy roots can be scraped clean and chewed on raw but are better boiled. They have a bland taste with hints of potato or corn like flavor. You can break up the fibers (the more the better) and then soak it in water, and pour off the water carefully when a bunch of starch has settled on the bottom of the pan. Then dry the resulting flour. It will not act like wheat flour because it has no gluten in it to make things rise, but it can be used for flatbreads or mixed with gluten based flour to make baked goods you want to rise.

Common Evening Primrose (Oenothera biennis) is a biennial herbaceous plant. The first year it makes a basal rosette and the second year it’ll grow a flowering stalk. Look for the red tinge in late winter on the leaves and the white central midrib. Use a trowel to dig up the root. Lightly scrape the dirt and outer skin on the root and you’ll see some red tinge up towards the top and a stringy woody core down the center. You can eat them raw or cook like a carrot. They have a touch of that peppery radish like heat when you eat them raw, less so in winter and early spring. It is a native plant so please pick sparingly with that conservation ethic or consider only as a survival resource.

Other plants that I find locally in wintertime include Stinging Nettle, Purple Dead Nettle, Mountain Mint and garlic mustard. I’ll continue to update this post as I have more encounters with these plants and document my wintertime uses.

David Alexander is author of the Buzz Into Action & Hop Into Action Science Curricula. He is passionate about making nature accessible to people and wildlife. You can follow him at www.natureintoaction.com

[…] but winter-specific guides or tips were sparse. That was until I came upon David Alexander’s Nature Into Action website. Alexander is a Northeast-based naturalist and nature enthusiast who frequently highlights […]